For the second time Dr. Eliyahu spoke at the Speakers’ Quarter of the Maastricht University Council about the Human Rights Due Diligence Committee, which the university intended to establish following protests against Israel by groups such as Free Palestine Maastricht.

Dear members of the University Council, dear colleagues and guests,

I am pleased and grateful for the opportunity to address you once again. After my previous submission, I did not have speaking rights. However, since certain comments were made about the concerns I raised, I requested the president of this council to address you again.

This may be the final time I speak before you on this matter, and I urge you to listen carefully—not just to my words, but to the implications of the decision before you.

This is not merely an administrative framework we are discussing today. It is a question of fairness, academic integrity, and whether Maastricht University will uphold its fundamental principles, or will we allow a tool of selective enforcement to dictate its academic partnerships.

The Selective Nature of the HRDD Framework

The last time I addressed the council; I raised serious concerns that the Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD) Framework is inherently discriminatory in its design and will inevitably be biased in application. This is because this entire framework, from its inception, was meant to target one country and one country only—Israel.

In short—this is not a bug; it is the defining feature of the HRDD framework. Without its discriminatory focus on Israel, this framework would not exist.

In response, I was told that this framework has been in development since September 2023. So the reason we are here today is supposedly completely unrelated to the genocidal attacks of Hamas and its collaborators on Israeli citizens on October 7 2023.

It was also argued that the HRDD tool will be applied to three different countries in its pilot phase. This response was meant to reassure me—and this Council—that the framework is not about Israel, that it is a neutral, systematic tool for assessing all partnerships. But let’s take a step back and ask a simple question: Does including two additional, undisclosed countries truly make the framework neutral? Or is this simply an attempt to provide a veneer of impartiality to a process that was always intended to scrutinize Israeli institutions more than any others?

Furthermore, throughout the process of developing this framework—one in which I and others have participated—we have repeatedly raised critical concerns that remain unaddressed. The most significant of these is the fact that this framework starts with a country analysis.

That means institutions are flagged not based on their own actions, but because of the country they are in. This contradicts the fundamental claim that the HRDD is an objective tool for evaluating institutional conduct.

The HRDD Framework: What It Claims vs. What It Does

The HRDD document states explicitly in Section 4.2 that "A partner is not held responsible for international crimes or serious violations of human rights committed by the national government or other non-state actors, in which it is not involved."

This principle, in theory, should prevent partnerships from being assessed on the basis of national affiliation. And yet, in practice, the framework does precisely that. Section 2.1 states that a “country analysis” is the first step in determining whether a partner should be investigated. Once a country is flagged, all institutions within it become subject to further scrutiny, regardless of their actual conduct.

This means that Israeli universities are not being assessed based on their individual policies, governance, or ethics. They are being examined because of their national identity. This is not just unfair—it is discriminatory.

And let’s be clear: We have repeatedly pointed this out during the development of the HRDD framework. Not once have we received a substantive response that explains how this does not constitute nationality-based discrimination, and neither has this council.

To summarize this point, you are asked to validate a nationally based discrimination, as stated in section 4.2 in the HRDD document, or if you like in the first and third bubbles.

A Framework That Cannot Be Universally Applied

If Maastricht University truly intended to apply this framework fairly, then it should be reviewing partnerships with universities in all countries where human rights concerns exist. That would mean subjecting institutions in China, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and many more to the same level of scrutiny.

However, this is not happening, and it never will. Maastricht University collaborates with institutions in many countries accused – the emphasis should be on this word: accused – of human rights violations, yet none of them are facing the kind of scrutiny being placed on Israel.

Would Maastricht University be willing to initiate an ethics review against academic institutions in the United States, knowing that it is frequently accused of human rights violations by international organizations? Would we accept potential sanctions against our own students and faculty in retaliation?

This is not an abstract concern. Given the political trajectory of the new U.S. administration, the actions it takes on the international stage, and the ongoing scrutiny of American universities for allowing antisemitism to flourish, the possibility of the HRDD framework being applied to U.S. institutions is very real.

And if it isn’t—if Maastricht University chooses to look the other way when it comes to certain countries while fixating on Israel—then the framework is not a human rights tool, but a political weapon.

Violation of Dutch and European Anti-Discrimination Laws

Throughout the development of this framework, we have also raised the issue of its legal standing. That issue has not been resolved. Under Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, discrimination on grounds of nationality is explicitly prohibited.

Likewise, Dutch anti-discrimination law prevents public institutions from treating entities differently based on nationality alone. Yet, the HRDD framework functions in a way that makes nationality the primary criterion for additional scrutiny. If this framework moves forward in its current form, it will place Maastricht University in direct violation of legal standards prohibiting such discrimination.

This is not a theoretical risk. It is a risk that we have raised repeatedly in discussions during the development of the HRDD tool. The fact that it has not been meaningfully addressed is deeply concerning.

A De Facto Boycott With Serious Consequences

By implementing the HRDD framework in its current form, Maastricht University is engaging in what is effectively a de facto boycott of Israeli institutions. This will not go unnoticed.

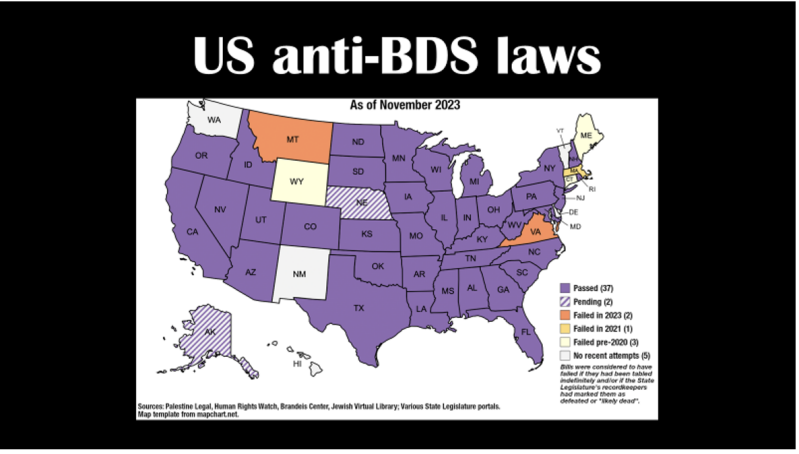

In the United States, 37 states have laws prohibiting state-funded institutions from engaging in boycotts against Israel. These laws are not symbolic—they have real consequences.

We have already seen this play out in practice. Ghent University in Belgium faced scrutiny from one of its American partners in Arizona after implementing policies seen as discriminatory toward Israeli academic institutions. The process is still ongoing but Ghent is now under its own scrutiny.

This is something we must prevent. This exercise in moral grandstanding, as our colleagues at Ghent are now learning, are likely to have serious consequences that may not be easily reversed.

If Maastricht University moves forward with this framework, it is only a matter of time before similar action is taken against UM by Israeli institutions and individuals on grounds of discrimination and damages, Dutch and EU regulators as well as U.S. universities bound by anti-BDS laws.

This could mean losing valuable research collaborations, funding opportunities, and academic exchanges. Maastricht prides itself on being an international university, but by adopting a discriminatory framework, it risks isolating itself from key global partners.

The Council’s Defining Choice

Members of the Council, you do not have the luxury of neutrality. A failure to reject this framework is an endorsement of discrimination, of a policy that violates Maastricht University’s legal obligations and core academic principles.

This is not just about Israel. It is about the precedent you set today. If you allow nationality-based discrimination in one instance, you open the door to it in others.

This council has a duty not just to consider the short-term pressures of the moment, but the long-term consequences of its decisions. You are not just making a recommendation—you are making a statement about the values this university stands for.

Rejecting this framework is not just an option; it is a necessity. A necessity to protect the university’s academic integrity, legal standing, and future. Anything less than a decisive negative recommendation would be a failure of responsibility.

I urge you: Make the right choice. Stand against discrimination. Protect Maastricht University from a grave mistake.

Allow a real dialogue!

Lastly, I want to acknowledge the established protocol, but I also want to respectfully point out a practical challenge. As in the previous meeting, my speaking time concludes immediately after this submission. Therefore, any feedback regarding the issues I raise will go unanswered.

To ensure a truly inclusive discussion, I request the council consider granting me the role of advisor oramicus curiae, so that I may represent and advocate for the seriously underrepresented viewpoint I bring.

Thank you.

Also read the first speech to the University Council of Maastricht University of Dr. Eliyahu Sapir here.

Reactie plaatsen

Reacties